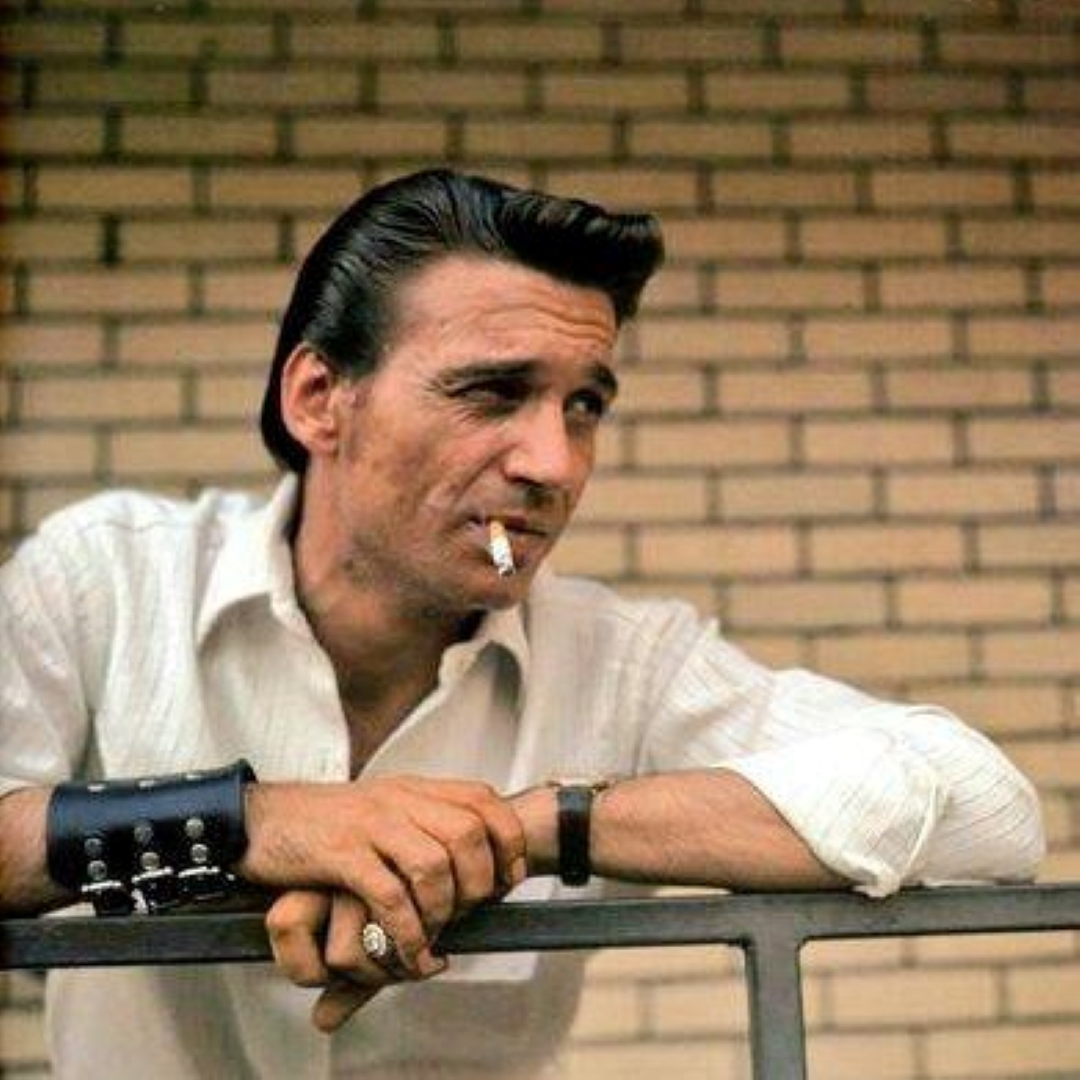

🌵 The Restless Boy from Texas

In the early 1960s, Waylon Jennings was a radio DJ in Lubbock, Texas—a small-town dreamer with a deep voice and an even deeper longing for something bigger. He’d already seen the bright lights once, as Buddy Holly’s protégé. Buddy had believed in him, had taken him under his wing, and even given him a Fender bass to play on tour.

Then came February 3, 1959—the day the music died. Waylon was supposed to be on that plane with Buddy, Ritchie Valens, and The Big Bopper. But he’d given up his seat. The guilt stayed with him for years. Every time he looked at a stage, he saw ghosts.

But music doesn’t let go of people like Waylon Jennings. It haunted him, pulled him back. He worked the late-night radio shifts, his voice a slow drawl across the desert air, spinning Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell records—and quietly writing songs of his own.

“That’s the Chance I’ll Have to Take” was born in that space: half defiance, half redemption. A song from a man who knew that chasing freedom could cost him everything.

🛣️ Breaking from the Nashville Machine

By 1965, Waylon had made his way to Nashville—the city of rhinestones and rules. He was signed to RCA Records, thanks to Chet Atkins, who believed in his voice but wanted him to “fit in.” They gave him the studio musicians, the same polished sound that ran through every record from Music Row.

It worked for some artists. But not for Waylon.

He felt caged in. The arrangements were clean, the lyrics tidy, the rebellion cut out with surgical precision. He’d look through the glass window of the RCA studio and think, “This ain’t me.”

When he wrote “That’s the Chance I’ll Have to Take,” it wasn’t just a love song—it was a personal manifesto. He sang of uncertainty, of walking away from comfort, of facing rejection head-on. It was his first quiet rebellion against the industry that tried to polish him into something he wasn’t.

Every word felt like it was addressed to Nashville itself:

“I’ve loved and lost and started over many times,

That’s the chance I’ll have to take.”

It wasn’t a hit. Not yet. But it was the first song where Waylon sounded like Waylon. Raw, restless, and unafraid.

🔥 Freedom Has a Price

For the next few years, Waylon fought a quiet war. He didn’t like being told what to wear, what to sing, or who should play on his records. Nashville had a formula, and Waylon didn’t fit it. He wanted his own band in the studio—his own sound, his own rhythm.

But every time he pushed back, RCA reminded him who paid the bills.

They said: “Waylon, this is how hits are made.”

And he’d reply: “Maybe so—but not by me.”

By the late ’60s, the stress took its toll. He was broke, overworked, addicted to pills just to stay awake. But deep down, he still believed in that first promise he’d made to himself—the promise in that 1965 song.

“That’s the Chance I’ll Have to Take” wasn’t just a title anymore. It was his code of survival. He’d rather lose everything than sing another song that wasn’t his own.

And soon enough, that stubbornness would pay off. Because within a decade, that same man—the one who once begged Nashville to listen—would become the outlaw who changed it forever.

🤠 The Birth of the Outlaw Spirit

Looking back, it’s almost poetic. That early single from 1965 was a quiet seed of what would bloom into the Outlaw Country movement a decade later.

When Waylon, Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, and Johnny Cash formed their brotherhood, they were fighting for one thing: freedom. The freedom to sound rough, to sing about life the way it really was, and to reject the shiny perfection of Nashville’s assembly line.

And Waylon had been preparing for that moment all along. Every lyric, every fight, every sleepless night in the studio—it all led back to that one decision he’d made in 1965: to take the chance.

When he finally gained full creative control in the early ’70s, he didn’t just record hits. He recorded truth.

Albums like Honky Tonk Heroes and Dreaming My Dreams weren’t just records—they were revolutions.

And somewhere inside those songs, you can still hear the echo of that younger Waylon, sitting in a Lubbock radio booth, staring at the desert night, whispering to himself:

“Freedom’s never free—but it’s worth every mile.”

“That’s the Chance I’ll Have to Take” might not top the charts today, but it remains one of the most prophetic moments in country history—the moment a man chose authenticity over applause, and in doing so, changed the genre forever.